Sunday, January 5th, 2020

John 1:1-14

“The Word that Was… Is Here”

Service Orientation: The One from the beginning is here and the light of this reality changes everything.

Memory Verse for the Week: John 1:1 – “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Background Information:

- The opening lines of the book of John draw us to the foundational truth of this Gospel and help us to view them from the widest possible perspective. Jesus, whom John commends to his readers as Savior of the world, must be linked to the great eternal reality (God), and the great temporal reality (God’s creation) if His salvation is to be of any value. (Joseph Dongell, John: A Commentary in the Wesleyan Tradition, 27)

- The Gospel mentions no author by name, but the evidence (both from textual and historical sources) points to John as the author. Certainly the writer had to be an eyewitness of the events and one of Jesus’ close associates. Irenaeus (A.D. 120—202) wrote, “Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon his breast, did himself publish a gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia.” John’s authorship of this Gospel was also affirmed by other early church fathers: Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Hippolytus, Justin Martyr, and Tertullian. Those who proposed a late writing (middle of the second century) were disproved when the Ryland Papyrus (a fragment of John’s Gospel) was discovered and dated from A.D. 110—125. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, xiv)

- John the Baptist is one of the most important persons in the New Testament. He’ is mentioned at least eighty-nine times. John had the special privilege of introducing Jesus to the nation of Israel. He also had the difficult task of preparing ‘the nation to receive their Messiah. He, called them to repent of their sins and to prove that repentance by being baptized and then living changed lives. (Warren W. Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary Vol. 1, 286)

- As far back as 560 B.C., Heraclitus had asked if there was anything permanent and lasting in the flux of constant change that was all about. His answer was that the Logos, the Reason of God, controlled and guided this stream of change. Later the Stoics held that Logos was the “mind of God,” the eternal principle of order in the universe, that which makes the chaos of the world a cosmos. If John had begun his Gospel by declaring that the Messiah had come it would have had little, if any, meaning for the Greeks. It was the Logos that became the point of contact, and opened the door for a hearing of the Gospel. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 30)

The question to be answered is…

What is this Word? And what does this Word have to do with life and light?

Answer…

By this Word all things exist and find their purpose. In this Word is life that lights up everything. This Word offers life and hope to all who believe. This Word is not a what, it’s a who, and this Word, is Jesus.

The word of the day is… Word

What’s significant about the Word John heralds?

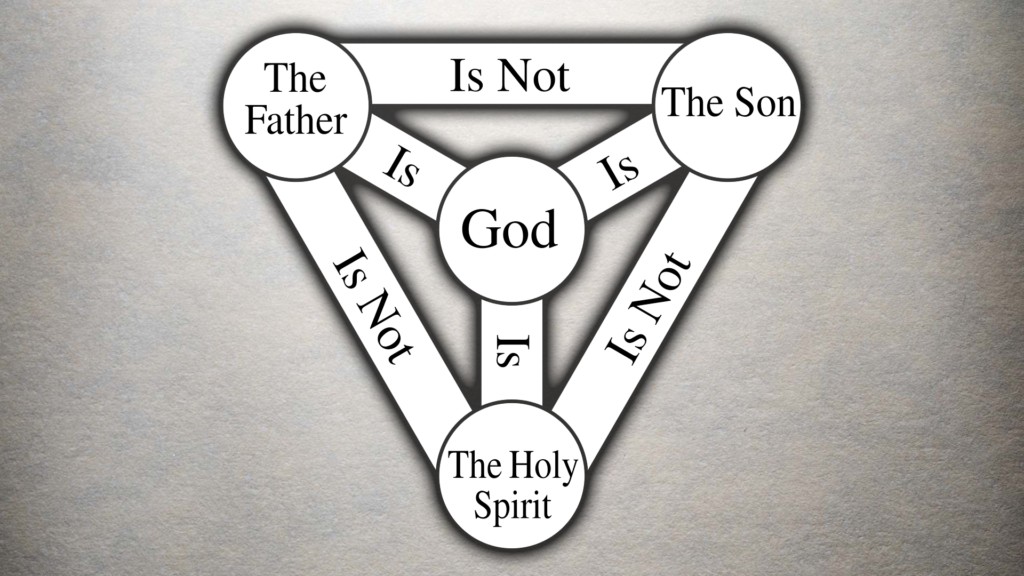

- The Word existed from eternity; in perfect union with God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

(Gen. 1:26; Dt. 6:4; Is. 9:6, 44:6; John 1:1, 3, 14; 1 Cor. 8:6; Eph. 4:4-6; Col. 2:9; 1 Tim. 2:5)

Yet the Word is not identical to God. The Greek grammatical construction of this phrase underlines this. Ordinarily the definite article ho is used before Theos, God. Had John done so here, he would have been saying the Word is identical with God. But he says the Word was Theos, with no definite article. Thus the noun, God, almost becomes an adjective. So John is saying that the Word was of the very essence, the very character, of God, while not being identical with God. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 34)

One of the most compelling reasons to believe the doctrine of the Trinity comes from the fact that it was revealed through a people most likely to reject it outright. In a world populated by many gods, it took the tough-minded Hebrews to clarify the revelation of God’s oneness expressed through Three-in-oneness. We humbly bow before the one God, but we do not presume to easily comprehend his essential being. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 3)

- The Word created and sustains all things.

(Gen. 2:7; Is. 55:11; John 1:3; 1 Cor. 8:6; Col. 1:16; Heb. 1:3)

He did not begin to exist when the heavens and the earth were made. Much less did he begin to exist when the gospel was brought into the world. He had glory with the Father ‘before the world was’ (John 17:5). He was existing when matter was first created, and before time began. He was ‘before all things’ (Col. 1:17). He was from all eternity. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 2)

- The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.

(Gen. 3:8; Is. 40:22; John 1:14; 2 Cor. 8:9; Phil 2:6-8; Heb. 1:1-4; 2:14)

John knows perfectly well he’s making language go beyond what’s normally possible, but it’s Jesus that makes him do it; because verse 14 says that the Word became flesh — that is, became human, became one of us. He became, in fact, the human being we know as Jesus. That’s the theme of this gospel: if you want to know who the true God is, look long and hard at Jesus. (N.T. Wright, John for Everyone, Part 1, 5)

- The Word offers light and life to all who believe.

(Gen. 15:6; John 1:4, 3:15, 16, 36, 6:35, 40, 47, 11:25, Rom. 4:17; 1 Tim. 1:16; 1 John 5:13)

John wrote this Gospel to meet the spiritual need of a church that had little background in the OT and that may have been endangered by the plausible contention of Cerinthus or men like him. John’s intention is stated with perfect clarity: “These [signs] are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31). The total thesis of the Gospel is belief in the Son who came from the Father. (Frank E. Gæbelein, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 9, 11)

What we believe concerning Jesus of Nazareth has tremendous consequence, and John is bent on convincing us that “Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God,” because the end of such believing is “that ye might have life through his name” (20:31 b) . Eternal life is in the question. The believing that he calls for, then, is something more than intellectual assent to a body of evidence; it carries with it a personal adjustment to the facts presented, which means in this case an acceptance of, and surrender to, Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord. This note of “life through believing” is one of John’s major themes, and most appropriately it is here stated as the end of his writing. (J.C. Macaulay, Expository Commentary on John, 12)

Conclusion…How does this Living Word effect my life?

A. This light and life is for all who believe.

(Acts 26:23; Rom. 13:12; 2 Cor. 4:6; Eph. 5:8, 9; 1 Thes. 5:5; 2 Tim. 1:10; 1 Pet. 2:9)

Every man that comes into this world is lightened by his Creator, but the natural man disregards this light, he repels it, and in consequence, is plunged into darkness. Instead of the natural man “living up to the light he has” (which none ever did) he “loves darkness rather than light” (John 3:19). Unregenerate man, then, is like one that is blind—he is in the dark. . . All other darkness yields to and fades away before light, but here “the darkness” is so impenetrable and hopeless, it neither apprehends nor comprehends. What a fearful and solemn indictment of fallen human nature! And how evident it is that nothing short of a miracle of saving grace can ever bring one “out of darkness into God’s marvelous light.” (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 26)

B. The light and life is for both now and forever.

(Gen. 2:7; John 3:15, 16, 36, 5:21, 24, 6:35, 40, 47, 48, Rom. 5:10, 17, 18, 21; 6:4, 8:2)

If we cannot or do not believe in Jesus’ true identity, we will not be able to trust our eternal destiny to him. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 1)

I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else. (C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory, 92)

C. Receiving the Living Word (Jesus) gives you the right to become a child of God.

(John 1:12-13, 12:36; Rom. 8:14, 16, 17, 19, 21, 9:8; Gal. 3:26, 4:7; 1 John 3:1-2)

All who welcome Jesus Christ as Lord of their lives are reborn spiritually, receiving new life from God. Through faith in Christ, the Holy Spirit changes us from the inside out—rearranging attitudes, desires, and motives. Being born makes us physically alive and places us in our parents’ family (1:13). Being born of God makes us spiritually alive and joins us with God’s family (1:12). The question then becomes, Have you received Christ in order that he can make you a new person? God makes this fresh start in life available to all who believe in Christ. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 9)

Worship Point…

Jesus is the living Word of God; life-giver and sustainer of all things. Knowing that God loved you so much to become what you are should compel you to worship Him.

Godliness means responding to God’s revelation in trust and obedience, faith and worship, prayer and praise, submission and service. Life must be seen and lived in the light of God’s Word. This, and nothing else, is true religion. (J.I. Packer, Knowing God, 20)

Gospel Application…

The God of the Universe loved us so much that He humbled himself to our level, lived life in a way we couldn’t, and died in our place so as to offer us new and eternal life as His children. This is GREAT news!

Given the significance of the “name,” it is clear that “life in his name” is another way of referring to being a child of God because it means sharing in the divine life (cf. 6:40) and reflecting God’s character. Thus the revelation of God in Jesus includes a revelation of the type of life we are offered as members of his family. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 57)

Spiritual Challenge Questions…

Reflect on these questions in your time with the Lord this week, or discuss with a Christian family member or life group.

- What can the light of Jesus reveal in people’s lives? What does it reveal in yours?

- What areas of darkness have you seen brought into the light, through the light of Jesus?

- What areas of darkness exist in your life that need exposure to The Light?

- What do you think the phrase life in his name means? What implications does that phrase hold for those who have received Jesus as their Lord and Savior?

Quotes to note…

Those who follow Christ are destined to bear his image, and to be the brethren of the first-born Son of God. Their goal is to become “as Christ.” Christ’s followers always have his image before their eyes, and in its light all other images are screened from their sight. (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship, 298)

The light will not shame you, if it shows you your own ugliness, and that ugliness so offends you that you perceive the beauty of the light. (Augustine, Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John, First Homily, as translated by John Burnaby, 262)

Countless people down the centuries have found that, through reading this gospel, the figure of Jesus becomes real for them, full of warmth and light and promise. It is, in fact, one of the great books in the literature of the world; and part of its greatness is the way it reveals its secrets not just to high-flown learning, but to those who come to it with humility and hope. (N.T. Wright, John for Everyone, Part 1, x)

Just as the Old Testament prophets made known that the Coming One should be a Man, a perfect Man, so did Messianic prediction give plain intimation that He should be more than a man. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 11)

“He was in the world.” Who was? None other than the One who had made it. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 28)

As the Word, the Son of God fully conveys and communicates God. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 2)

Faith alone is that evidence, that conviction, that demonstration of things invisible, whereby the eyes of our understanding being opened, and divine light poured in upon them, we “see the wondrous things of Gods law;” the excellency and purity of it; the height, and depth, and length, and breadth thereof, and of every commandment contained therein. It is by faith that, beholding “the light of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ,” we perceive, as in a glass, all that is in ourselves, yea, the inmost motions of our souls. (John Wesley, Sermons on Several Occasions, 107)

FURTHER QUOTES AND RESEARCH:

This Gospel states its purpose clearly: “But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31). Two questions will shape the following discussion: What does this statement of purpose itself mean? And what does the larger content of the Gospel imply regarding its purpose? Any reading of the purpose statement will conclude that “believing” lies at its heart. This believing calls not for a general hopefulness or optimism regarding life, nor even for a belief in the existence of God (that is presumed). Rather, this faith is the expression of confidence in a particular truth: that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God. The whole gospel narrative provides supporting proofs for this claim, and supplies examples of persons who have come to know Jesus and the truth about Him. (Joseph Dongell, John: A Commentary in the Wesleyan Tradition, 19)

Because all human beings experience the same sequence of physical birth, life, and death, regardless of their spiritual condition before God, it is tempting to imagine that physical and spiritual death operate on separate, unrelated tracks. While this may be undeniable within the scope of present human experience, Scripture views the matter from a higher altitude and tells a different story: Physical death results not merely from “natural” processes of disease and decay, but from a spiritual rebellion at the very fountainhead of the human race. In a profound way, every human death, even the death of a saint, is the outworking of a primitive sin which has infected the whole creation (see Romans 5). (Joseph Dongell, John: A Commentary in the Wesleyan Tradition, 34-35)

The purpose of the Baptist’s mission was both simple and broad: That through him all men might believe (John 1:7b). Here for the first time we encounter one of the central themes of this entire Gospel— believing. Believing proves itself to be right at the core of the Evangelist’s message, not only because of its high frequency of occurrence (over one hundred times), but because of its place in the stated purpose of the Gospel: “But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (20:31). (Joseph Dongell, John: A Commentary in the Wesleyan Tradition, 38)

This Gospel is first and foremost a message of evangelism, carefully and creatively written, that men may come to have life in the name of Jesus, the Christ, the Son of God. This is John’s declared purpose (John 20:31), so the constant question throughout is the identity of the man Jesus. By what authority does He speak and minister? At the outset the writer makes the awesome theological affirmation that this man is the eternal Word who has been with God and who is God and who has now become flesh. In saying that Jesus is the Word, John is appealing with great imagination and force to both Jews and Greeks. For both, this concept had a unique and powerful meaning. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 18)

Is there any way one can plumb the depths of John’s prologue to his Gospel? Such intense power in so few words! After brooding over the meaning of these short verses for months, I am more reluctant than ever to put my thoughts on paper. Yet, strangely, I am eager and compelled to do so. I can readily understand why both Augustine and Chrysostom are reported as saying, “It is beyond the power of man to speak as John does in his prologue.” John Calvin has written of the prologue, “Rather should we be satisfied with this heavenly oracle, knowing that it says much more than our minds can take in”. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 27)

John begins with a disarmingly simple phrase, “In the beginning was the Word.” Here is the central theme, the grand motif, of the symphony which will come pouring forth with such glory throughout the Gospel narrative. The “Speech Of God” John Calvin called it. What a wonder that God should speak. Here is a mystery, not unlike speech among us humans, that unique capacity to use signs and symbols, sounds and touch, and even silence, to communicate with one another. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 28)

But when John speaks of “the Word,” he is taking us far beyond the meaning it has for us in general. He is a Hebrew speaking to his own people, and for them, the Word had unique power. For these people, there was a precious quality, a living reality, about words, so they were used sparingly. There were only ten thousand words in Hebrew speech and only two hundred thousand words in the Greek language. The Semitic root for “word,” dabar, also meant “thing,” “affair, “event,” or “action.” A word spoken was a happening. Once it had been uttered, it could not be torn from the event that it evoked. Thus, when Isaac had blessed Jacob and then later discovered that Jacob had cleverly stolen his twin brother Esau’s birthright, he could not recall his words of blessing, even though Esau pleaded with his aged father to do this. The words had gone forth and the blessing stood. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 29)

Little wonder then that when John wrote, “In the beginning was the Word,” he evoked a whole cluster of memories among his Hebrew readers and touched a nerve of understanding. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 30)

John, the writer, was the son of Zebedee, a fairly prosperous Galilean fisherman, through and through a Jew. Nourished on the Law and Prophets, all the Jewish customs and traditions had shaped John’s deepest inner life. There is no way he can shake off or dismiss those roots, nor should he. This is why his appeal to this Gentile audience is so remarkable. Adolf Schlatter has argued persuasively in Der Evangelist Johannes (1930) that “the writer thought in Semitic idiom while he wrote in Greek.” (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 31)

However, in becoming flesh, the Word did not cease to be God. There is a unity in His person before and after the Incarnation. He is divine. Yet He became flesh. By this act, He became subject to all the conditions of human existence—the weakness, dependence, and mortality which is our common lot. He was subject to temptation, and He could have sinned. His humanity is real and complete. All through this Gospel, we see both His human weakness and His divine majesty. The eternal Word and the Jesus of history are one. There is a mystery here beyond which we cannot go. Suffice it to say that our only hope of sharing in the life of God is that the Word has really become flesh. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 43)

But now God has come to dwell among His people, in His Living Word. Not at the edge of life, for a passing time, but at the center of everything, in the flesh of Jesus, for all time. Those who believe become the abiding place for the Living Word. The company of believers now become the tabernacle, the body in which the Living Word can dwell through His Spirit. God has guaranteed His presence, His settling down permanently in one place, as the Word dwells in us. There is a glory in the Word dwelling among us. This is the visible presence of God among men. (Roger L. Fredrikson, The Communicator’s Commentary: John, 45)

This Gospel was probably written at a time when the church was composed of second and third-generation Christians who needed more detailed instruction about Jesus and new defenses for the apologetic problems raised by apostasy within the church and by growing opposition from without. The understanding of the person of Christ that had depended on the testimony of his contemporaries was becoming a philosophical and theological problem. Doctrinal variations had begun to appear, and some of the assertions of the basic Christian truths had been challenged. A new presentation was necessary to meet the questions of the changing times. As the Gospel states, “These things are written that you may maintain your belief that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God” (20:31). (Frank E. Gæbelein, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 9, 4)

The earliest tradition of the church ascribes the fourth Gospel to John the son of Zebedee, one of the first of Jesus’ disciples, and one who was closest to him. Irenaeus bishop of Lyons (fl. c. 180) stated plainly that “John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon his breast, had himself published a Gospel during his residence in Ephesus in Asia” (Against Heresies 3. l). Irenaeus’s testimony has been corroborated by Other writers. (Frank E. Gæbelein, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 9, 5)

Probably it will not be too wrong to suggest that the Gospel of John was written for Gentile Christians who had already acquired a basic knowledge of the life and works of Jesus but who needed further confirmation of their faith. By the use of personal reminiscences interpreted in the light of a long life of devotion to Christ and by numerous episodes that generally had not been used in the Gospel tradition, whether written or oral, John created a new and different approach to understanding Jesus’ person. John’s readers were primarily second-generation Christians he was familiar with and to whom he seemed patriarchal. If the Johannine Epistles are any guide, the writer must have been a highly respected elder within the structure of the church. John considered himself responsible for its welfare and did not hesitate to assert his authority. (Frank E. Gæbelein, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 9, 10)

Some scholars think the Gospel was written before the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70 (Morris 1971:30-35; Robinson 1976:254-84; 1985:67-93). Since most scholars agree that John did not use the Synoptic Gospels themselves as source material, it is possible to argue that John goes back to source as directly as the Synoptics (Robinson 1985). If that is the case, then there is no reason to expect a long period of writing while sources were gathered. On this theory he did not use the Synoptics because they were being written at the same time he was writing. Furthermore, the presence of many features of pre-70 conditions in Israel, not least the presence of the temple, suggest an early date. There is no clear indication in this Gospel that the temple has been destroyed. A statement like that made by Caiaphas (11:48) is quite in keeping with a pre-70 context. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 25)

We are at the outset of a story that will reveal to us the most profound mysteries of life. This story is simply about God, the glory of his character, the nature of his life and his desire to share that life with his creatures. It is about God come amongst us and the mixed response he received to his offer of divine life. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 49)

John’s opening echoes Genesis (Gen 1: 1), but whereas Genesis refers to the God’s activity at the beginning of creation, here we learn of a being who existed before creation took place. In the beginning the Word already was. So we actually start before the beginning, outside of time and space in eternity. If we want to understand who Jesus is, John says, we must begin with the relationship shared between the Father and the Son “before the world began” (Jn 17:5, 24). This relationship is the central revelation of this Gospel and the key to understanding all that Jesus says and does. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 49-50)

To speak of the Word (logos) in relation to the beginning of creation would make sense to both Jews and Greeks. In some schools of Greek thought, the universe is kosmos, an ordered place, and what lies behind the universe and orders it is reason (logos). For the Jews, creation took place through God’s speech (Gen 1; Ps 33:6). Furthermore, in John’s day “word” was often associated with “wisdom” (for example, Wisdom of Solomon 9:1; cf. Breck 1991:79-98), and John will often use wisdom motifs to speak of Jesus (cf. Willett 1992). (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 50)

By stating both positively and negatively that the Word is the agent of all creation (1:3), John emphasizes that there were no exceptions: the existence of absolutely all things came by this Word. Although with verse 3 we move from eternity to creation, we are still dealing with facts hard to comprehend. Until discoveries made in the 1920s, the Milky Way was thought to be the entire universe, but now we realize there are many billions of galaxies. Science is helping us spiritually, for it silences us before God in wonder and awe. But this verse also helps us put science in its proper place. The universe is incredibly wonderful, so how much more wonderful must be the one upon whose purpose and power it depends. “The builder of a house has greater honor than the house itself’ (Heb 3:3). (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 51)

His life, manifest in the incarnation, is our light (Jn 1:4). In this Gospel light always refers to the revelation and salvation that Jesus is and offers (cf. 8:12; 11:9 is the one exception). In order to have life we need to know God, and Jesus is our source of such knowledge. As our light, his life is our guide. He is our wisdom, that which reveals all else to us and enables us to see. In Jewish thought it is the law that plays this role (for example, Wisdom of Solomon 18:4; cf. Hengel 2:112; Kittel 1967:134-36), but for John it is the incarnation of the Word that makes sense of all of life. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 52)

So the question of why some believe and others do not is answered by another of John’s antinomies. There is no doubt that God’s gracious sovereign initiative comes first, for he is the source of all life and it is only by his grace that any life occurs and abides at all. The right (or power) to become children of God must be given by God. The images of verse 13 rule out any role for human power or authority in the process of becoming a child of God. But unlike in natural birth the one being born of God does play a part; this life is not forced on the believer but must be received. Those who are receptive to the Son are offered the gift of becoming children of God themselves. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 56)

On the human side everything depends on one’s response to the light who has come. (Rodney A. Whitacre, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: John, 56)

Approaching John’s gospel is a bit like arriving at a grand, imposing house. Many Bible readers know that this gospel is not quite like the others. They may have heard, or begun to discover, that it’s got hidden depths of meaning. According to one well-known saying, this book is like a pool that’s safe for a child to paddle in but deep enough for an elephant to swim in. But, though it’s imposing in its structure and ideas, it’s not meant to scare you off. It makes you welcome. Indeed, millions have found that, as they come closer to this book, the Friend above all friends is coming out to meet them. (N.T. Wright, John for Everyone, Part 1, 2)

This book is about the creator God acting in a new way within his much-loved creation. It is about the way in which the long story which began in Genesis reached the climax the creator had always intended. (N.T. Wright, John for Everyone, Part 1, 3)

Each book of the Bible has a prominent and dominant theme which is peculiar to itself. Just as each member in the human body has its own particular function, so every book in the Bible has its own special purpose and mission. The theme of John’s Gospel is the Deity of the Saviour. Here, as nowhere else in Scripture so fully, the Godhood of Christ is presented to our view. That which is outstanding in this fourth Gospel is the Divine Sonship of the Lord Jesus. In this Book we are shown that the One who was heralded by the angels to the Bethlehem shepherds, who walked this earth for thirty-three years, who was crucified at Calvary who rose in triumph from the grave, and who forty days later departed from these scenes, was none other than the Lord of Glory. The evidence for this is overwhelming, the proofs almost without number, and the effect of contemplating them must be to bow our hearts in worship before “the great God and our Saviour Jesus Christ” (Titus 2:13). (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 10)

How entirely different is this from the opening verses of the other Gospels! John opens by immediately presenting Christ not as the Son of David, nor as the Son of man, but as the Son of God. John takes us back to the beginning, and shows that the Lord Jesus had no beginning. John goes behind creation and shows that the Saviour was Himself the Creator. Every clause in these verses calls for our most careful and prayerful attention. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 18)

“In the beginning” is something we are unable to comprehend: it is one of those matchless sweeps of inspiration which rises above the level of human thought. “In the beginning was the word,” and we are equally unable to grasp the final meaning of this. A “word” is an expression: by words we articulate our speech. The Word of God, then, is Deity expressing itself in audible terms. And yet, when we have said this, how much there is that we leave unsaid! “And the word was with God,” and this intimates His separate personality, and shows His relation to the Other Persons of the blessed Trinity. But how sadly incapacitated are we for meditating upon the relations which exist between the different Persons of the Godhead. “And God was the word. Not only was Christ the Revealer of God, but He always was, and ever remains, none other than God himself. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 18-19)

That it is here said “the word was with God” tells of His separate personality: He was not “in” God, but “with” God. Now, mark here the marvelous accuracy of Scripture. It is not said, “the word was with the Father” as we might have expected, but “the word was with God.” The name “God” is common to the three Persons of the Holy Trinity, whereas “the Father” is the special title of the first Person only. Had it said “the word was with the Father,” the Holy Spirit had been excluded; but “with God” takes in the Word dwelling in eternal fellowship with both the Father and the Spirit. Observe, too, it does not say, “And God was with God,” for while there is plurality of Persons in the Godhead, there is but “one God,” therefore the minute accuracy of “the WORD was with God.” (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 22)

“And the word was made (became) flesh, and dwelt among us” (1:14). Infinite became finite. The Invisible became tangible. The Transcendent became imminent. That which was far off drew nigh. That which was beyond the reach of the human mind became that which could be beholden within the realm of human life. Here we are permitted to see through a veil that, which unveiled, would have blinded us. “The word became flesh:” He became what He was not previously. He did not cease to be God, but He became Man. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 32)

In His marvelous stoop we behold His glory. Greatness is never so glorious as when it takes the place of lowliness. Power is never so attractive as when it is placed at the disposal of others. Might is never so triumphant as when it sets aside its own prerogatives. Sovereignty is never so winsome as when it is seen in the place of service. And, may we not say it reverently, Deity had never appeared so glorious as when It hung upon a maiden’s breast! Yes, we behold His glory — the glory of an infinite condescension, the glory of a matchless grace, the glory of a fathomless love. (Arthur W. Pink, Exposition of the Gospel of John, 41)

John stands as a great example of Christ’s power to transform lives. Christ can change anyone—no one is beyond hope. Jesus accepted John as he was, a Son of Thunder, and changed him into what he would become, the apostle of love. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, xii)

John provides a powerful example of a lifetime of service to Christ. As a young man, John left his fishing nets to follow the Savior. For three intense years he watched Jesus live and love, and listened to him teach and preach. John saw Jesus crucified and then risen! John’s life was changed dramatically, from an impetuous, hot-tempered youth, to a loving and wise man of God. Through it all, John remained faithful, so that at the end of his life, he continued to bear strong witness to the truth and power of the gospel. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, xiv)

How strong is your commitment to Christ? Will it last through the years? The true test of an athlete is not in the start but the finish. So too with faithfulness to Christ—how will you finish that race? (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, xiv)

In both the Jewish and Greek conceptions, logos conveyed the idea of beginnings—the world began through the Word (see Genesis 1:3ff., where the expression “God said” occurs repeatedly). John may have had these ideas in mind, but his description shows clearly that he spoke of Jesus as a human being he knew and loved (see especially 1:14), who was at the same time the Creator of the universe, the ultimate revelation of God, and also the living picture of God’s holiness, the one in whom “all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17 NIV). Jesus as the logos reveals God’s mind to us. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 3)

1:2 The second verse of the prologue underscores the truth that the Word coexisted with the Father from the beginning. A wrong teaching called the “Arian heresy” developed in the fourth century of Christianity. Arius, the father of this heresy, was a priest of Alexandria (in Egypt) during the reign of Emperor Constantine. He taught that Jesus, the Son of God, was not eternal but was created by the Father. Therefore, Jesus was not God by nature; Christ was not one substance with the Father. He also taught that the Holy Spirit was begotten by the logos. Arius’s bishop, Alexander, condemned Arius and his followers. But Arius’s views gained some support. At the Church Council in Nicea in 325 A.D., Athanasius defeated Arius in debate and the Nicene Creed was adopted, which established the biblical teaching that Jesus was “one essence with the Father.” Yet this controversy raged until it was defeated at the Council of Constantinople in 381 A.D. This heresy still exists, however, in several so-called Christian cults. Yet John’s Gospel proclaims simply and clearly that the Son of God is coeternal with the Father. 4 (Incidentally, St. Nicholas punched Arius in the face over this issue at the council of Nicea.)

What is seen by the light of Jesus? When Christ’s light shines, we see our sin and his glory. We can refuse to see the light and remain in darkness. But whoever responds will be enlightened by Christ. He will fill our minds with God’s thoughts. He will guide our path, give us God’s perspective, and drive out the darkness of sin. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 5)

There is enough light for those who only desire to see the light, and enough darkness for those who only desire the contrary. Blaise Pascal

1:7-8 He came as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him.NRSV

John the Baptist’s function was to be a channel whereby people could come to Christ. Jesus called John the Baptist the greatest man ever born (Luke 7:28) because he fulfilled the highest privilege; he was the first to point people to Christ, so in a very real sense, all who have come to believe have done so because of his witness. He was first in a line of witnesses that stretches through the centuries to this day. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 7)

Man does not recognize the place he should fill. He has obviously gone astray. He has fallen from the true status, and he cannot find it again. So he searches everywhere anxiously but in vain, in the midst of great darkness. Blaise Pascal

1:11 He came to His own.NKJV

In Greek this reads, “He came to his own things”—that is, he came to that which belonged to him. The expression can even be used to describe a homecoming. This phrase intensifies the description of Christ’s rejection. Jesus was not welcome in the world, or even his home. His own refers to God’s chosen nation, Israel, which was particularly Christ’s. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 8)

His own did not receive Him.NKJV According to the Greek, this means that his own family did not receive him. The Greek word for receive means “to welcome.” The Jews did not welcome Jesus. Those who should have been most eager to welcome him were the first to turn away. As a nation, they rejected their Mes- siah. This rejection is further described at the end of Jesus’ minis- try (12:37-41). Isaiah had foreseen this unbelief (Isaiah 53:1-3). In spite of the rejection described here, John steers clear of passing sentence on the world. Instead, he turns our attention on those who did welcome Christ in sincere faith. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 8)

The two most common errors that people make about Jesus are minimizing his humanity or minimizing his divinity. Jesus is both divine and human (see Philippians 2:5-9). (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 11)

Underneath Jesus’ appearance as an ordinary Jewish carpenter, the disciples saw the indwelling glory of God. To the outsider, Jesus was nobody special; to those in the inner circle, he was the unique Son of God filled with glory. Too often we accuse the disciples of being slow to understand Jesus, but much of the time they were simply stunned. Jesus was always more than they could absorb. He will have the same effect on us. (Bruce B. Barton, Life Application Bible Commentary, 12)

St. John tells us, that ‘in him was life, and the life was the light of men.’ He is the eternal fountain, from which alone the sons of men have ever derived life. Whatever spiritual life and light Adam and Eve possessed before the fall, was from Christ. Whatever deliverance from sin and spiritual death any child of Adam has ever enjoyed since the fall, whatever light of conscience or understanding anyone has obtained, all has flowed from Christ. The vast majority of mankind in every age have refused to know him, have forgotten the fall, and their own need of a Saviour. The light has been constantly shining ‘in darkness.’ The most have ‘not comprehended the light.’ But if any men and women out of the countless millions of mankind have ever had spiritual life and light, they have owed all to Christ. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 2-3)

If no one less than the Eternal God, the Creator and Preserver of all things, could take away the sin of the world, sin must be a far more abominable thing in the sight of God than most men suppose. The right measure of sin’s sinfulness is the dignity of him who came into the world to save sinners. If Christ is so great, then sin must indeed be sinful! (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 3)

The substance of this Gospel is, for the most part, peculiar to itself. With the exception of the crucifixion, and a few other matters, the things which St John was inspired to record concerning our Lord, are only found in his Gospel. He says nothing about our Lord’s birth and infancy,—his temptation,—the Sermon on the Mount,— the transfiguration,—the prophecy about Jerusalem, and the appointment of the Lord’s supper. He gives us very few miracles, and even fewer parables. But the things which John does relate are among the most precious treasures which Christians possess. The chapters about Nicodemus,—the woman of Samaria,—the raising of Lazarus, and our Lord’s appearance to Peter after his resurrection at the Sea of Galilee,—the public discourses of the fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, and tenth chapters,—the private discourses of the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth chapters,—and, above all, the prayer of the seventeenth chapter, are some of the most valuable portions of the Bible. All these chapters, be it remembered, we owe to St John. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 4)

v1 The truth contained in this sentence, is one of the deepest and most mysterious in the whole range of Christian theology. The nature of this union between the Father and the Son we have no mental capacity to explain. Augustine draws illustrations from the sun and its rays, and from fire and the light of fire, which, though two distinct things, are yet inseparably united, so that where the one is the other is. But all illustrations on such subjects halt and fail. Here, at any rate, it is better to believe than to attempt to explain. Our Lord says distinctly, ‘I am in the Father and the Father in me.’ ‘I and my Father are one.’ ‘He that hath seen me hath seen the Father’ (John 14:9-11; John 10:30). Let us be fully persuaded that the Father and the Son are two distinct persons in the Trinity, co-equal and co-eternal,—and yet that they are one in substance and inseparably united- and undivided. Let us grasp firmly the words of the Athanasian Creed: ‘Neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the substance.’ But here let us stop. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 6)

Christ is to the souls of men what the sun is to the world. He is the centre and source of all spiritual light, warmth, life, health, growth, beauty, and fertility. Like the sun, he shines for the common benefit of all mankind,—for high and for low, for rich and for poor, for Jew and for Greek. Like the sun, he is free to all. All may look at him, and drink health out of his light. If millions of mankind were mad enough to dwell in caves underground, or to bandage their eyes, their darkness would be their own fault, and not the fault of the sun. So, likewise, if millions of men and women love spiritual 10

‘darkness rather than light,’ the blame must be laid on their blind hearts, and not on Christ. ‘Their foolish heart was darkened’ (John 3:19; Rom. 1:21). But whether men will see or not, Christ is the true sun, and the light of the world. There is no light for sinners except in the Lord Jesus. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 11)

This union of two natures in Christ’s one person is doubtless one of the greatest mysteries of the Christian religion. It needs to be carefully stated. It is just one of those great truths which are not meant to be curiously pried into, but to be reverently believed. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 18)

Though he became ‘flesh’ in the fullest sense, when he was born of the Virgin Mary, he never at any period ceased to be the Eternal Word. To say that he constantly manifested his divine nature during his earthly ministry, would, of course, be contrary to plain facts. To attempt to explain why his Godhead was sometimes veiled and at other times unveiled, while he was on earth, would be venturing on ground which we had better leave alone. But to say that at any instant of his earthly ministry he was not fully and entirely God, is nothing less than heresy. (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts on John Vol.1, 19)

This Gospel also tells the story of a new community. Jesus chooses a few ordinary men and shares His life with them so deeply that they will manifest the glory and love of the Father. They are called to love one another as Jesus loves them. That loving unity will reflect the intimate relationship between the Father and the Son, which both call and judge the world. They will be a people bearing “the name”; for the mission which the Son has been given by the Father is now given to His disciples. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 19)

There are two overwhelming reasons for accepting the beloved disciple as the author of this Gospel. One is the way natural, intimate details are almost casually included in the whole account. Only a person living with Jesus on a day-to-day basis could easily include this kind of personal detail. Someone writing “from the outside” would have included more contrived, obvious details. Furthermore, we must take quite seriously the writer’s conscious inclusion of him- self in speaking of his own witness. ‘ ‘We beheld His glory” (John 1:14), and ‘ ‘He who has seen has testified, and his testimony is true” (John 19:35), illustrate John’s own involvement as a firsthand witness.

The second reason is that the early church fathers, those who lived closest to the time when the New Testament was written, are almost unanimous in their claim that John the Beloved is the writer of the Gospel that bears his name. Westcott voices the understanding of a number of commentators: “But it is most significant that Eusebius, who had access to many works which are now lost, speaks without reserve of the Fourth Gospel as the unquestioned work of John, no less than those three great representative Fathers who sum up the teaching of the century.”3 These were Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian. And it is almost certain that John had been living in Ephesus, a great Hellenistic center, for a considerable time when this Gospel was written. Surely in this inquisitive, sophisticated, cosmopolitan culture John had been opened up, had been internationalized, so that he saw the history of Jesus through the eyes of the larger world. He would always be a fisherman from Galilee, but he also had become a citizen of a city influenced by Greek culture. The Lord had schooled John for the writing of this particular Gospel. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 19-20)

Is there any way one can plumb the depths of John’s prologue to his Gospel? Such intense power in so few words! After brooding over the meaning of these short verses for months, I am more reluctant than ever to put my thoughts on paper. Yet, strangely, I am eager and compelled to do so. I can readily understand why both Augustine and Chrysostom are reported as saying, “It is beyond the power of man to speak as John does in his prologue.” John Calvin has written of the prologue, “Rather should we be satisfied with this heavenly oracle, knowing that it says much more than our minds can take in.” (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 27)

Words can fulfill or hurt or bless. They can build up or tear down. There are those tender, healing, affirming words, “Welcome home.” “Congratulations, it’s a girl.” “I love you.” Or those angry, destructive, cutting words, “Divorce is granted.” “I hate you.” “She’s dead.” What meaning they carry—far more than mere sounds in the air. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 29)

All through the Gospel, John shares helpful insights for his Greek audience. Here is a true evangelist establishing rapport and trust. John did not try to force his Greek readers into an alien point of view, but rather sought to lead them into investigating seriously who Jesus was. This is why that simple invitation Jesus gave the first disciples, “Come and see,” is an opportunity for all readers to check out the evidence. How could the Logos and “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” be one and the same? Surely that kind of honest invitation would appeal to the Greek mind. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 31)

This “life was the light of men. ” At creation God said, ” ‘Let there be light’; and there was light” (Gen. 1:3). Out of the very life of God, light shines forth to dispel the chaos and darkness. That light is in man in a particular way. The Lord God has breathed into him His own breath of life. An intimate, personal act which sets man apart, making him uniquely responsible to his Maker. That breath is the source of reason, conscience, and the longing to love and worship— the light that makes us human. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 36)

However, in becoming flesh, the Word did not cease to be God. There is a unity in His person before and after the Incarnation. He is divine. Yet He became flesh. By this act, He became subject to all the conditions of human existence—the weakness, dependence, and mortality which is our common lot. He was subject to temptation, and He could have sinned. His humanity is real and complete. All through this Gospel, we see both His human weakness and His divine majesty. The eternal Word and the Jesus of history are one. There is a mystery here beyond which we cannot go. Suffice it to say that our only hope of sharing in the life of God is that the Word has really become flesh. (Roger L. Fredrikson, Mastering the New Testament: John, 43)

Now this is something quite interesting, and it is not true of physical light. You go into a dark room, and the minute you switch on the light, the darkness leaves, it disappears. Darkness and light cannot exist together physically. The moment you bring light in, darkness is gone. The minute light is taken out, darkness will come right back in. But spiritual light and darkness exist together. Sometimes there is a husband who is saved and a wife who is unsaved—or vice versa. Here is a believer working next to another man who says, “What do you mean when you talk about being a Christian? I do the best I can. Am I not a Christian?” There you have light and darkness side by side and the darkness just cannot take it in. That is exactly what is said here, “The light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.” (J. Vernon McGee, Thru The Bible Commentary Series, John, 28)

Notice that this is for “them that believe on his name.” And always with the word “believe” there is a preposition. You see, faith, as the Bible uses it, is not just head knowledge. Many people ask, “You mean all that I have to do is to say I believe?” Yes, that is all you have to do, but let’s see what that implies. With the verse “to believe” there is always a preposition—sometimes en (in), sometimes eis (into), or sometimes epi (upon). You must believe into, in, or upon Jesus Christ. Let me illustrate with a chair. I am standing beside a chair and I be- lieve it will hold me up, but it is not holding me up. Why? Because I have only a head knowledge. I just say, “Yes, it will hold me up.” Now suppose I believe into the chair by sitting in it. See what I mean? I am committing my entire weight to it and it is holding me up. Is Christ holding you up? Is He your Savior? It is not a question of standing to the side and saying, “Oh, I believe Jesus is the Son of God.” The ques- tion is have you trusted Him, have you believed into Him, are you rest- ing in Him? This chair is holding me up completely. And at this moment Christ is my complete Savior. I am depending on Him; I am resting in Him. (J. Vernon McGee, Thru The Bible Commentary Series, John, 30)

Personal communion is indicated in the statement, “And the Word was with God.” We believe that God is one, but His oneness is not the solitariness of the unitarian conception. The Word is coeternal with God, realizes personal communion with God, and that communion is eternal as the being of God. There is but one possible conclusion from these two statements, and the apostle John does not hesitate to enunciate it—”And the Word was God.” This coexistence and this communion are not between two things, but within one being. Christ did not become God at some point in time, but this interrelation of personality is inherent in the eternal being of God. Thus Eternity, Personality, and Deity are fully attributed to our Lord. This is a moment, not for speculation, but for worship. (J.C. Macaulay, Expository Commentary on John, 15)

This eternal, creative Word is also the living Word. ‘ ‘In him was life” (John 1:4a) . Life with Him is not derived, but native. He is the source and fountain of all life, of whatever kind, however expressed. All the “new life” that we see manifesting itself in the spring of the year is from Christ. Our own life is borrowed from Him. But this life in Christ is something to man that it cannot be to beast or flower: “the life was the light of men” (1:4b) . There is not a man in all the earth who is utterly devoid of this light. He may not have received “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor 4:6b) . He may lack the moral training that many of us boast; he may even be doing his utmost to smother the light; but it is there, and it persists. Even in the darkest heart it shines out its defiance of the darkness, and the darkness can never utterly obliterate it. Received, it is “the light of life”; refused, it is the light of condemnation. (J.C. Macaulay, Expository Commentary on John, 16)

God has never left himself without a witness. (J.C. Macaulay, Expository Commentary on John, 18)

Despite all the assaults of darkness on God’s revelation, it is unextinguished and inextinguishable. The powers of darkness have tried many weapons, and at times the light has been obscured almost to eclipse, only to break out again in new glory and splendor. There have been fogs and clouds and mists, but fogs have a way of lifting, clouds of breaking, and mists of dispelling. We think of the Dark Ages, when the pall of Rome lay heavy upon a darkened Europe, and again of the desolations of deism in the eighteenth century; but the Reformation and the evangelical revival were God’s effective answers. “The light shineth in darkness, and the darkness overcame it not.” Did you ever know when the darkness in your room failed to flee before the switching on of your electric light? It is so in the spiritual world. Light may be rejected, but it cannot be extinguished. Received, it will save; refused, it will consume. But it will always triumph. (J.C. Macaulay, Expository Commentary on John, 19)